Greenside Lead Mine in Patterdale

Patterdale Township circa 1900.

The White Lion is on the left.

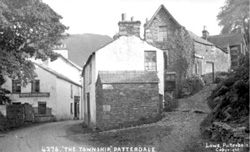

The White Lion Inn (left) in about 1900

Early convict ship like the Susan

Besides being a cracking pint, good place to stay (I have) and with a hunting tradition as long as your arm, The White Lion in Patterdale has an interesting history. The following piece was “lifted” off the Grisedale family web site. I emailed a request to use it but never got a reply.... so bugger it, we can always take it off.

"Oh Lord, I’m Killed, He Has Stabbed Me”

On 26 February 1836 a twenty-two year old Cumberland lead miner called John Greenwell stepped ashore in the Australian penal colony of Sydney from the convict ship Susan. The voyage had taken 114 days and there had been a serious outbreak of scurvy which had taken the lives of several convicts. John knew he would never return to England as he was a convicted murderer. At his trial for murder in Appleby in Westmorland John was found guilty and sentenced to be hanged, but at the last minute this was commuted to transportation to Australia for life. And who had John killed? The answer is that he had repeatedly stabbed Thomas Grisdale of Patterdale, the son of local Hartsop Hall farmer Robert Grisdale, and Thomas had died of his wounds within the hour.

Before I tell the full story of Thomas Grisdale’s murder let us say something of the circumstances. John Greenwell was a lead miner in the Greenside ‘silver-lead’ mine in Patterdale. He had been born in 1814 in another lead mining village—Alston in Cumberland—but the Greenside mine was flourishing and miners like John came from all over to work there. The miners lived in appalling conditions in the mine ‘lodging shops’.

Before there was a smelting mill at Greenside, ‘the metal, after being washed, was put into bag holding about 1 cwt. each. The whole was carted to Penrith, where it was met by a string of horses and carts and conveyed to Alston, where it smelted, and eventually from there put on the market’.

The miners only got paid twice a year; they had to go to the Angel Inn in Penrith, ‘where the agent (Mr. Errington) attended to pay the men’.

The miners, some accompanied by their wives, used to walk into Penrith. Others came by boat to Pooley, there being no ‘Raven‘ or ‘Lady of the Lake‘ in those days; whilst others came in carts—conveyances, or light carts as they were called, being very scarce in the country at that time.

From there they would head back to Patterdale to settle their bills in the mine’s ‘shop’ and of course to spend a lot in the local inns.

Mr. Cant’s shop on Patterdale miners’ pay day used to be like a fair, almost all the miners being supplied with provisions by him throughout the six months, their ‘better halves’ putting in an appearance on pay days to straighten up their shop bill.

It was after one of these pay days that John Greenwell and some of his mining friends were drinking in the White Lion Inn in Patterdale ‘Township’.

The later Rector of Patterdale, the Rev W. P. Morris, wrote in The Records of Patterdalein 1903:

These pay visits continued until the year 1835, when a serious misfortune took place at Patterdale amongst some of the miners. It was always surmised that there was a little jealousy amongst the natives, and a parishioner was stabbed to death. The sad affair took place on a Sunday night (March 8th, 1835), when two miners, one named Joseph Bainbridge and the other Greenwell, both natives of Alston, had been down into what is termed the ‘Township’ (in the White Lion Inn), and whilst there had got into a quarrel with some of the residents. After dark they started for the mines, and whilst traversing one of the lanes leading out of Patterdale, they went into the dyke to cut themselves each a thick stick to provide weapons of defence should their assailants trouble them again. While in the hedge someone approached, and Greenwell, thinking it was one of their opponents, rushed out at him and stabbed him in the abdomen with the clasp-knife he was using. He turned out not to be a miner at all, but a young parishioner returning to his home.

The two miners were tried at Appleby Spring Assizes in the year 1836 (actually 1835). Bainbridge was acquitted and Greenwell was sentenced to death, but was reprieved and sentenced to penal servitude for life. Greenwell was a quiet young man about 20 years of age, of light build, and bore an excellent character. Bainbridge was a powerful fellow, a kind-hearted chap, but rather rough in his manner, and somewhat quarrelsome when he had any drink. After his release he went into Durham to work in the coal pits, and I have heard my brother John, who lived at Hartlepool, say that he was one of the best coal hewers in the county.

After the affair the officials thought it prudent and more safe to pay the men at the mines and not bring them into Penrith, hence the abandonment of Patterdale pay days at Penrith.

But is this what really happened? It was not. There are many reports describing the trial and the testimony of the witnesses called. Here is just one published in 1836 in The Annual Register… of the year 1835. It gives the full story.

13 March – Murder – Appleby –

John Greenwood was indicted for the wilful murder of Thomas Grisdale at Patterdale on the 8th March.

George Greenhill disposed that on the Sunday preceding he and the deceased went to the White Lion public-house in Patterdale. There were many persons in the house, and among them a young man named Bainbridge and the prisoner Greenwell. There was a great deal of noise, but the deceased was very quiet and took no part in it. Greenwell quarrelled with a man named Rothey, and they had a little fight or scuffle for about five minutes. They both went down on the floor.

The deceased lifted them up, and seemed desirous to part them. After they had got up, Bainbridge and the prisoner Greenwell said they would fight any two men in the dale. The deceased said very good-naturedly, that if it was day-light he would take both of them, and he would then in the house, if anybody would see fair play.

After this Bainbridge and Greenwell became so troublesome, that the landlord put them out. In the course of a little time the latter returned, and was again thrust out, but in these matters the deceased did not interfere. In the mean time the witness and two lads went out of the house with the deceased. Soon after, they saw Bainbridge call Greenwell to the end of the house, and they procured each a stick, about a yard long, and a little thicker than a walking stick. They came running towards these three, who ran out of their way for some distance, when the deceased, having not retreated awhile, said, “I have not melt (meddled) with them, why should I run away?” and stopped.

The witness ran on about twenty yards further, and then stopped also. On turning his head, he saw the prisoner Greenwell run up to the deceased, and make a push at his belly, and then at his breast near the neck. The deceased seized the prisoner by the collar and pushed him away, and then put one hand to his belly, and the other to his breast, saying, “Oh Lord, I’m killed, he has stabbed me”.

Witness and his companions then ran up to him, and the prisoner ran away. They soon after found the prisoner lying besides the wood, and told him to get up and go before them to the King’s Arms public-house in Patterdale. Being afraid of him, they told him to throw away what he had, and he threw a pipe from his pocket. They followed him, and he was taken into custody.

The next morning a knife was found at the place where the prisoner had lain down, which was bloody. It appeared in subsequent evidence that the knife belonged to Bainbridge, but had been borrowed by the prisoner just before the commission of the fatal deed. A surgeon was sent for to the deceased, who was taken to the White Lion, where he died in three quarters of an hour.

John Chapman and Thomas Chapman, two witnesses who were with Greenhill, corroborated his testimony, which also confirmed as to several points by other witnesses, without varying the general features of the case. The surgeon stated that either of the wounds was sufficient to cause death, and he could not state which was in fact the cause of the death as distinct from the other.

In summing up the evidence the learned Judge defined the distinction between murder and manslaughter upon provocation, and put before them all the circumstances in the case which had any tendency to justify the more merciful conclusion; but after a short retirement the jury found the prisoner Guilty of wilful murder.

Sentence of death was then pronounced upon the prisoner, and the execution ordered to take place the following Monday.

Obviously the Judge was somewhat sympathetic toward Greenwell and before the coming Monday he was reprieved and sentenced to life in penal servitude in Australia.

Thomas’s Hartsop Hall ‘respectable’ farming family was devastated, their son was only twenty-seven. He was, reported the Kendal Mercury, ‘… sober in his habits… extensively known and greatly esteemed’. They buried him in Patterdale Churchyard, ‘close to where the old church stood’, on March 12th, 1835, erecting a tombstone which reads:

To the memory of Thomas, son of Robert and Elizabeth Grisdale of Hartsop Hall, who was brutally murdered by an unprovoked assassin on the evening of Sunday, March 8th, 1835, aged 27 years.

It continues:

By man’s worst crime he fell and

not his own,

Belov’d he lived and dying left a name,

With which his parents mark this votive stone,

The grief is theirs, th’ assassin bears the shame.

Better to sleep tho’ in an early grave,

Than like the murder’r Cain exist a banished slave.

For more about the family see The Grisdales of Patterdale and Hartsop and From Matterdale to Alberta – the story of the English past of one Canadian Grisdale family and Robert Grisdale’s Escape.

And what of John Greenwell, the ‘murder’r Cain’, who would lead his life like a ‘banished slave’?

After his reprieve from death, John would have first spent some time in prison in Westmorland before being sent to a hellish Prison Hulk anchored at Woolwich outside London. The surgeon of the convict ship Susan, Thomas Galloway, kept a Medical Journal from 12 September 1835 to 26 February 1836. He tells us ‘of the three hundred convicts embarked, 200 were taken on board at Woolwich and 100 at Sheerness’, before departing from Portsmouth for Australia on 16 October 1835—it arrived in Port Jackson (Sydney) on 7 February 1836 with 294 male prisoners aboard.

Galloway tells both of the scurvy and that: ‘There were several men who had very recently been in Hospital for various illnesses and who concealed this at the time of the surgeon’s examination because of their desire to proceed to New South Wales. Also several old and very infirm men who had to be kept entirely on the Hospital Provision. Ophthalmia was not confined to the prisoners and several of the seamen were also affected as well as Officers of the Guard.’

As well as the 294 male convicts:

A detachment of the 28th Regiment arrived by the prison ship Susan. They were Landed at the dock yard in Sydney on Friday afternoon 12th February and marched to the barracks. The band did not meet them as was usual on such occasions. Some of the 28th who arrived on the Susan included Captain George Symons, Private James Flanagan, Private John Mooney, Private Henry Gunter, Private William Gollett, Private Walter Williams. Other convict ships bringing detachments of the 28th regiment included the Charles Kerr, Westmoreland, Marquis of Huntley, Norfolk, Backwell, England, John Barry, Waterloo, Moffatt, Strathfieldsaye, Portsea and Lady McNaughten.

But the convicts would have had a different welcome. First an ‘indent’ was taken so that if they escaped they could be identified. John Greenwood is described as 22, 5ft 7.5 inches, of ‘ruddy’ complexion, brown hair, with eyes ‘hazel and inflamed’. He had : ‘Hairy mole right ear, mole under left ear, ears pierced for rings, mole above right elbow, three scars back little finger right hand, and three on thumb, scar cap of left knee.’ Pretty much like all Australians then!

I know only a little about what happened to John, suffice it to say that in 1848 after twelve years of penal servitude he was granted a ‘conditional pardon’ by the governor of New South Wales Sir Charles Fitz Roy. He was free to stay and work at his trade in Australia but could never return to Britain. As a miner did he go off to the new gold ‘diggings’, we don’t know.

And here I will end except for one thing. The two old photographs of the White Lion Inn in Patterdale where Thomas Grisdale was murdered were taken by Patterdale photographer Joseph Lowe around 1900. They are the oldest photographs of Patterdale and Joseph’s wife was Jessie Grisdale, the great granddaughter of Robert Grisdale of Hartsop Hall, murdered Thomas’s father!